The Divine Symbols of Dionysus

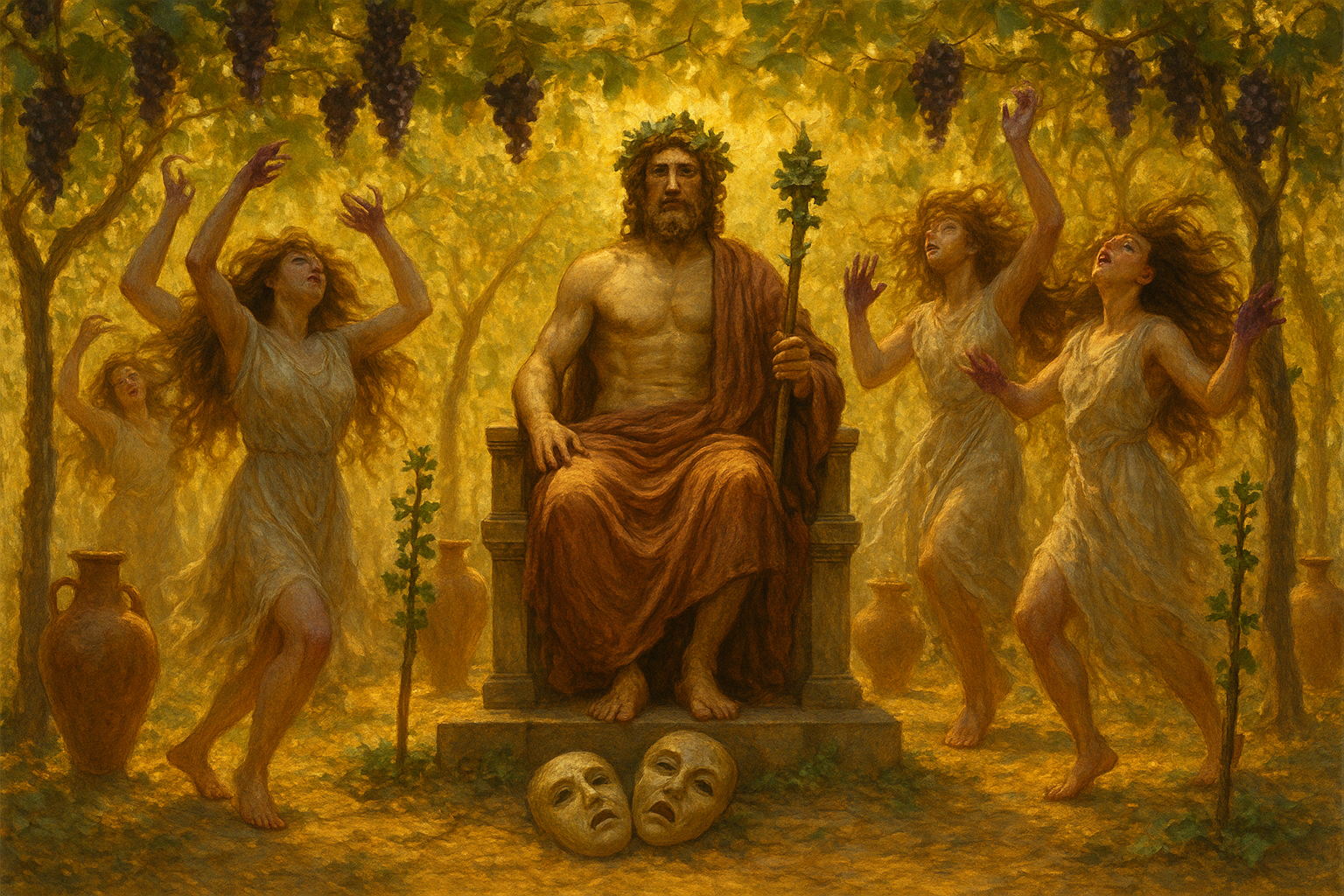

Dionysus stands among the most complex deities in the Greek pantheon. His symbols tell stories of transformation, ecstasy, and divine power. These sacred emblems appeared consistently across ancient art, literature, and religious practices.

Visual Symbols That Defined the Wine God

Ancient Greek artists developed a sophisticated visual language to represent Dionysus, creating instantly recognizable symbols that appeared across:

- Temple frescoes depicting religious ceremonies

- Pottery designs used in daily life and ritual contexts

- Theatrical masks worn during dramatic performances

- Coins and medallions circulated throughout the Mediterranean

The Sacred Vine and Its Transformative Power

The grapevine served as Dionysus’s most prominent attribute, but its significance extended far beyond simple agricultural association. In Greek artistic tradition, the vine represented:

- Metamorphosis – The transformation of simple fruit into intoxicating wine

- Cyclical renewal – Annual death and rebirth of the plant

- Divine connection – The bridge between earthly pleasure and spiritual transcendence

Artists frequently depicted Dionysus crowned with ivy wreaths, another climbing plant that remained green throughout winter, symbolizing eternal life and the god’s triumph over death.

Animal Companions as Divine Messengers

The leopard and panther became central to Dionysiac iconography, representing the god’s wild, untamed nature. These feline companions appeared in artwork as:

- Mounts carrying Dionysus across distant lands

- Guardians flanking his throne

- Symbols of the primal forces unleashed during religious ecstasy

Goats and bulls also featured prominently, connecting Dionysus to fertility rites and sacrifice rituals that formed the backbone of his worship.

The Thyrsus: More Than a Simple Staff

Perhaps no symbol carried more complex meaning than the thyrsus – a staff topped with a pinecone and wrapped in ivy. This seemingly simple object represented:

Masculine and feminine duality – The phallic staff combined with the fertile pinecone Nature’s abundance – Pine cones as symbols of regeneration and growth

Divine authority – The staff as a scepter of spiritual power

Devotees carried these staffs during Dionysiac festivals, using them in ecstatic dances that could reportedly work miracles or strike down enemies.

Cultural Context Behind the Symbols

Each iconographic element reflected deeper societal tensions within ancient Greek culture:

- The tension between civilization and wildness

- The balance of order and chaos in community life

- The relationship between mortality and divine experience

These symbols weren’t merely decorative – they served as visual theology, communicating complex religious concepts to both literate and illiterate populations across the ancient world.

The Thyrsus: Staff of Divine Power

The thyrsus represents Dionysus‘s most recognizable attribute. This ceremonial staff topped with a pinecone symbolized fertility and transformation. Ancient Greeks carried these staffs during Dionysiac festivals and rituals.

Crafted from fennel stalks, the thyrsus demonstrated the god’s connection to nature’s cycles. Furthermore, the pinecone crown represented masculine fertility and regeneration. Devotees believed the staff channeled divine energy during religious ceremonies.

The Thyrsus in Ancient Visual Culture

The thyrsus served as Dionysus’s primary symbol of divine power across the ancient Mediterranean, appearing with remarkable consistency in artistic representations spanning over a millennium. This sacred staff, topped with a pinecone and wrapped in ivy vines, became one of the most recognizable religious symbols of the classical world.

Artistic Representations Across Media

Vase Paintings and Pottery

- Red-figure and black-figure pottery from Athens frequently showcase Dionysus gripping his thyrsus during mythological scenes

- Drinking vessels (kylixes and kraters) often featured the god using his staff to transform pirates into dolphins or to strike down those who opposed his worship

- The thyrsus appears in over 2,000 surviving Greek vase paintings, making it one of the most documented divine attributes in ancient art

Monumental Sculpture

- Roman copies of Greek statues consistently depict Dionysus leaning casually on his thyrsus, emphasizing both his divine authority and relaxed nature

- The famous Dionysus of Knidos shows the god’s thyrsus as tall as his shoulder, carved with intricate ivy leaf details

- Temple pediments and friezes across Greece and Asia Minor feature the thyrsus as a key identifying element in Bacchanalian scenes

Frescoes and Wall Paintings

- Pompeii’s Villa of Mysteries contains stunning frescoes where initiates hold thyrsus staffs during mysterious religious ceremonies

- Roman domestic art frequently incorporated thyrsus motifs in dining rooms, connecting the symbol to wine, celebration, and hospitality

- Egyptian-Greek fusion art from Alexandria shows Dionysus-Osiris figures wielding hybrid thyrsus-was scepters

The Thyrsus in Religious Practice

Sacred Processions and Festivals

- Dionysiac processions featured hundreds of worshippers carrying miniature thyrsus staffs made from fennel stalks

- Festival celebrations during the Greater Dionysia included theatrical performances where actors portraying satyrs brandished decorative thyrsus props

- Mystery cult initiations required participants to craft their own personal thyrsus as part of the sacred ritual process

Regional Variations

- Thracian followers created thyrsus staffs using local pine species and mountain ivy

- Italian Bacchants incorporated grape clusters alongside the traditional pinecone topping

- Asian Minor devotees sometimes added colorful ribbons and small bronze bells to their ceremonial staffs

Symbolic Power and Religious Authority

The thyrsus represented far more than a simple ceremonial object—it embodied divine transformation and the god’s ability to blur boundaries between civilization and wildness. Ancient sources describe how Dionysus could use his thyrsus to:

- Strike rocks and cause wine or honey to flow forth

- Touch the ground and make grapevines instantly sprout

- Transform enemies into wild beasts or drive them to madness

- Heal the sick and restore fertility to barren lands

This powerful symbolism explains why the thyrsus became such a dominant visual element in ancient art, serving as an immediate identifier of Dionysiac power and presence across diverse cultural contexts throughout the classical world.

Sacred Vessels: The Kantharos Cup

The kantharos served as Dionysus’s drinking vessel of choice. This distinctive cup featured high handles and a deep bowl perfect for wine consumption. Ancient Greeks associated this vessel exclusively with their wine god.

Pottery workshops throughout Greece produced kantharoi in various sizes and decorative styles. Consequently, these cups became symbols of divine communion with Dionysus. Worshippers used them during religious banquets and sacred ceremonies.

Archaeological discoveries reveal kantharoi in temples, homes, and burial sites across the ancient world. Source These findings demonstrate the cup’s importance in both religious and daily life.

Nature’s Crown: Ivy and Grapevines

Ivy wreaths adorned Dionysus’s head in most artistic representations. This evergreen plant symbolized eternal life and divine protection. Ancient Greeks viewed ivy as sacred to their wine god because it remained green year-round.

The Sacred Symbolism of Dionysus and the Vine

The profound relationship between Dionysus and grapevines extends far beyond simple association—it represents the very essence of transformation and divine power in ancient Greek culture. This botanical connection served as both literal representation and powerful metaphor for the god’s influence over human experience.

Artistic Depictions and Visual Traditions

Ancient artists developed sophisticated visual languages to capture Dionysus’s vineyard dominion:

- Classical pottery featured the god crowned with elaborate grape-leaf wreaths, his curly hair intertwined with delicate tendrils

- Marble sculptures depicted him holding massive grape clusters, juice seemingly dripping from his divine fingers

- Fresco paintings in Roman villas showed Dionysus reclining beneath sprawling vineyard canopies, surrounded by dancing satyrs harvesting the sacred fruit

- Mosaic floors illustrated his triumphant processions with grape vines forming decorative borders and background elements

The Deeper Symbolism of Viticulture

The grapevine’s annual cycle perfectly mirrored Dionysus’s mythological journey:

- Winter dormancy represented his death and descent into the underworld

- Spring budding symbolized his resurrection and return to life

- Summer growth embodied his wild, untamed energy spreading across the land

- Autumn harvest culminated in the transformation of simple fruit into intoxicating wine

Sacred Geography and Wine Regions

Dionysus’s influence extended across the Mediterranean through specific vineyard locations:

- The island of Naxos, where he discovered Ariadne, became renowned for its exceptional wine production

- Mount Nysa, his mythical birthplace, was said to produce grapes with supernatural properties

- Ancient Thrace and Macedonia were considered his earthly kingdoms, their robust red wines reflecting his passionate nature

The Mystical Process of Fermentation

To ancient Greeks, fermentation itself was divine magic—the mysterious transformation of sweet grape juice into mind-altering wine could only be explained through Dionysus’s direct intervention. This process represented:

- The death of the grape and its rebirth as something more powerful

- The invisible forces of the god working within earthly vessels

- The bridge between mortal and divine consciousness through intoxication

Both plants demonstrated Dionysus’s power over growth and transformation. Indeed, ivy’s ability to climb and cover structures mirrored the god’s transformative influence. Similarly, grapes underwent miraculous change from fruit to intoxicating wine.

Seasonal Symbolism

Ivy’s evergreen nature contrasted beautifully with the seasonal cycle of grapevines. This combination represented both eternal divine presence and cyclical renewal. Ancient worshippers understood these botanical symbols as expressions of cosmic balance.

Ritual participants wore ivy crowns during Dionysiac festivals. Meanwhile, grape harvest celebrations honored the god’s gift of wine to humanity. These seasonal observances strengthened the connection between natural cycles and divine power.

Wild Companions: Leopards and Panthers

Feline companions frequently accompanied Dionysus in ancient artistic depictions. Leopards and panthers represented the wild, untamed aspects of his divine nature. These powerful predators symbolized the god’s ability to inspire both ecstasy and terror.

The Leopard’s Sacred Journey: Dionysus and His Feline Companions

The connection between Dionysus and big cats runs far deeper than mere artistic symbolism—it represents a fundamental aspect of the god’s divine nature and mythological journey. Ancient Greek storytellers wove intricate tales of the wine god’s Eastern expeditions, particularly his legendary conquest of India, where he encountered the magnificent leopards that would forever change his divine image.

The Indian Campaign: Where God Met Beast

According to classical sources, Dionysus’s triumphant Indian campaign lasted several years, during which he:

- Conquered vast territories across the subcontinent

- Introduced viticulture and wine-making to new civilizations

- Assembled an exotic retinue of followers and sacred animals

- Established his divine authority through spectacular displays of power

The leopard-drawn chariot became the ultimate symbol of this victory—not simply a mode of transportation, but a declaration of divine conquest over the wild and untamed forces of nature.

Symbolic Significance in Ancient Art

Greek artists and craftsmen embraced these feline motifs with remarkable creativity, incorporating leopards into:

Religious Artifacts:

- Temple friezes depicting Dionysiac processions

- Sacred vessels used in wine ceremonies

- Votive offerings dedicated to the god

Decorative Arts:

- Mosaic floors in wealthy homes

- Painted pottery showing mythological scenes

- Jewelry featuring leopard-spotted patterns

The Leopard as Divine Metaphor

The association transcended mere decoration—leopards embodied key aspects of Dionysus’s character:

- Wildness and Untamed Power: Like the god himself, leopards represented forces beyond conventional control

- Exotic Mystery: Their foreign origins mirrored Dionysus’s role as an outsider deity

- Dangerous Beauty: The combination of grace and lethality reflected the dual nature of wine and ecstasy

This rich symbolic language allowed ancient Greeks to understand their complex relationship with a god who brought both divine inspiration and potential destruction.

The spotted coats of leopards and panthers suggested transformation and change. Their ability to move between light and shadow mirrored Dionysus’s dual nature as both civilizer and wild force. Artists used these animals to convey the god’s complex personality.

Fertility Symbols and Sacred Imagery

Phallic imagery appeared prominently in Dionysiac art and ritual contexts. These symbols represented fertility, creative power, and life force. Ancient Greeks viewed such imagery as sacred expressions of divine generative energy.

Herms bearing phallic symbols marked boundaries of Dionysiac sacred spaces. Additionally, processions featured large phallic objects carried by celebrants. These displays honored the god’s role in ensuring agricultural and human fertility.

Modern audiences may find such imagery surprising, but ancient Greeks considered it deeply religious. The symbols connected Dionysus to fundamental life forces and cosmic creativity. Furthermore, they emphasized his power over reproduction and abundance.

Ritual Context

In the vibrant tapestry of ancient Greek worship, the advent of spring festivals dedicated to Dionysus was far more than mere celebration; it was a profound, communal invocation of life itself. These rituals were meticulously timed to coincide with the earth’s dramatic reawakening after winter’s slumber, marking a pivotal moment when the dormant land stirred with renewed promise.

Here’s a deeper look into the significance and practices surrounding these vital spring rites:

- The Earth’s Rebirth and Dionysus’s Domain

- Dionysus, often celebrated as the god of wine, was fundamentally linked to the entire cycle of vegetation and fertility. He embodied the surging sap in the vines, the budding leaves, and the flourishing of all plant life.

- His festivals, therefore, were not just for the grapes, but for the general agricultural productivity—ensuring bountiful harvests of grain, olives, and fruits, alongside the proliferation of livestock crucial for survival.

- Emblematic Fertility Symbols Beyond the Obvious

- While phallic imagery held a prominent place, the spectrum of fertility symbols was rich and diverse.

- Vines and Ivy: These plants, sacred to Dionysus, symbolized persistent life and intoxicating growth. Participants often adorned themselves with ivy wreaths, embodying the god’s wild, untamed energy.

- Thyrsi: The pinecone-tipped staffs carried by Dionysian revelers were potent symbols of fertility, representing the pine tree’s regenerative power and the intoxicating properties of its sap.

- Animals: Bulls, goats, and sometimes snakes were also associated with Dionysus, representing primal virility, sacrificial offerings, and the chthonic forces of the earth that drive growth.

- The Sacred Phallus: A Profound Petition for Abundance

- Far from being crude, the ritualistic display of phallic imagery was a deeply sacred and communal act. Large, often elaborately decorated, wooden or clay phalluses were carried in processions (Phallophoria), serving as direct, tangible representations of the male generative principle.

- Sympathetic Magic: This wasn’t merely a static symbol; it was a performative prayer, a ritualistic act of sympathetic magic. By displaying and honoring this powerful image, participants believed they could actively encourage and draw forth the same life-giving force into their fields, their herds, and their families.

- A Multi-faceted Prayer for Abundance:

- Agricultural Prosperity: To ensure the land would be fertile, yielding abundant crops and rich harvests.

- Human Procreation: To bless couples with healthy children, sustaining family lines and the community’s future.

- Communal Well-being: To infuse the entire community with human vitality—not just physical health, but also vigor, joy, and a release from inhibitions that fostered social cohesion and creative energy.

- Ecstatic Release and Renewal

- The festivals were characterized by ecstatic revelry, music, dance, and dramatic performances. This collective catharsis was believed to connect participants directly with Dionysus’s untamed spirit, mirroring and stimulating the earth’s own awakening. It was a time to shed the constraints of everyday life and tap into a primal, regenerative energy.

Through these deeply symbolic and participatory rituals, ancient Greeks actively engaged with the divine forces of nature, seeking to guarantee the continued flow of life, prosperity, and joy for their world.

Delving deeper into the Dionysiac rites, it becomes clear that women were not merely participants but often the central figures in the fertility-focused aspects of the god’s worship. Their perceived intrinsic connection to life-giving and nurturing made them ideal conduits for invoking Dionysus’s generative power, particularly in a society deeply reliant on agricultural abundance and the continuation of family lines.

Women’s Pivotal Roles in Ritual

The involvement of women in these ceremonies was multifaceted and deeply symbolic, extending beyond simple attendance:

- Guardians of Sacred Objects: Women were entrusted with carrying and presenting various sacred implements vital to the rituals. These often included:

- The thyrsus: A staff wreathed with ivy and topped with a pinecone, symbolizing fertility and intoxication.

- The cista mystica: A sacred chest, often containing cult objects like a phallus (representing generative power) or snakes (symbols of regeneration).

- Kraters: Large mixing bowls used for wine, central to Dionysiac revelry and communal sharing.

- Ritual masks: Worn to embody deities or spirits, facilitating a connection to the divine.

- Performers of Ecstatic Dance: The dances performed were far from mere entertainment; they were powerful acts of invocation. Through rhythmic movement, often accompanied by music (flutes, drums, cymbals) and chanting, women aimed to achieve a state of ecstatic trance. This altered state was believed to open a direct channel to Dionysus, allowing his blessings to flow into the community. These dances mimicked natural cycles of growth and abundance, embodying the very fertility they sought to invoke for:

- Bountiful harvests: Ensuring healthy crops, particularly grapes (Dionysus’s primary domain), but also grains and other produce.

- Prosperous families: Blessing women with fertility, safe childbirth, and the healthy growth of children, thereby securing the future of the community.

Strengthening Community and Honoring the Divine

These ceremonies served as powerful pillars of ancient Greek society, weaving together spiritual devotion with social cohesion:

- Communal Bonding: The shared experience of ritual participation, often culminating in communal feasting and the consumption of wine, fostered strong bonds among women and the wider community. It was a collective endeavor where individual identities merged into a unified purpose, reinforcing social structures and mutual support.

- Divine Veneration: Beyond the practical requests for fertility, the rituals were profound acts of honoring Dionysus. Participants acknowledged his immense power over life, death, and rebirth; his ability to bring both ecstatic joy and terrifying madness; and his role as a god who dissolves boundaries. The women’s devotion was a testament to the community’s deep respect and awe for this complex and transformative deity.

- Spiritual Renewal: Through their active roles, women facilitated a spiritual renewal for the entire community, reaffirming their connection to the natural world, the divine realm, and each other. This collective spiritual engagement was essential for maintaining cultural identity and resilience.

Theatrical Connections and Dramatic Arts

Masks became essential symbols linking Dionysus to theatrical performance. Ancient Greeks credited him with inspiring dramatic arts and stage entertainment. Theater festivals honored the god through competitive performances and elaborate celebrations.

The iconic twin visages of the theatrical masks, Thalia (the smiling muse of comedy) and Melpomene (the weeping muse of tragedy), are far more than mere stage props; they are profound emblems of the Dionysian spirit and a window into ancient Greek understanding of the human condition.

The Spectrum of Dionysian Ecstasy and Agony

Dionysus, the god of wine, revelry, and ecstatic liberation, brought forth moments of unbridled euphoria. His festivals, like the vibrant Dionysia, were spectacles of communal joy, where inhibitions dissolved, and the spirit soared through:

- Wine-fueled revelry: A release from daily concerns, fostering a sense of unity and liberation.

- Ecstatic dance and music: Allowing participants to transcend their mundane selves and connect with the divine.

- Fertility and abundance: Celebrating the life-giving forces of nature and the promise of renewal.

The comedic mask, with its wide, often exaggerated grin, perfectly encapsulated this release, representing the triumph of life, fertility, and the sheer delight of existence. It symbolized the joyous embrace of chaos and the freedom found in abandoning oneself to the moment.

Yet, woven into this tapestry of joy was an inescapable thread of pathos and profound sorrow. Dionysus himself experienced:

- Dismemberment and rebirth: A violent cycle reflecting the natural world’s death and renewal.

- Divine madness: A state of extreme mental and emotional turmoil, both terrifying and inspiring.

- Exile and wandering: Highlighting themes of loneliness and the search for acceptance.

The tragic mask, often depicting anguish, contemplation, or a silent scream, served as a stark reminder of life’s fleeting nature, its inevitable pains, and the deep emotional wells of human experience—loss, grief, and the struggle against fate. It confronted the audience with the harsh realities of mortality and the consequences of hubris or destiny.

Dionysus: A God of Contradictions

This intricate dance between elation and despair wasn’t just a human observation; it was intrinsically embedded in the very fabric of Dionysus’s mythos. He was a god of liminal spaces, existing between:

- Civilization and wilderness: Bringing order through chaos.

- Sober reason and intoxicated madness: Where divine inspiration often bordered on delusion.

- Life and death: The twice-born god, embodying resurrection and the cyclical nature of existence.

His journey, marked by both persecution and triumphant worship, demonstrated a deity who intimately understood—and embodied—the full spectrum of emotional extremes. His stories taught that one cannot exist without the other; the sweetness of joy is often intensified by the memory or threat of sorrow.

Masks as Metaphors for the Human Condition

Therefore, these theatrical symbols transcended simple representations of genre. They became potent metaphors for the unpredictable tapestry of human existence. Life, as the ancient Greeks understood it through Dionysus, is not a linear path of constant happiness or unending despair, but rather a dynamic interplay where:

- Laughter often precedes tears: Highlighting the transient nature of all feelings.

- Moments of profound grief can give way to renewed hope: Emphasizing resilience and the capacity for change.

- True understanding comes from embracing both extremes: Acknowledging that joy and sorrow are not opposites but two sides of the same coin.

By donning these masks, actors could embody the universal human condition, allowing audiences to witness and process emotions too overwhelming for everyday life. The stage became a sacred space where the full, often contradictory, spectrum of human feeling could be explored and cathartically experienced, fostering a deeper empathy and understanding of our shared emotional landscape. These masks weren’t just about showing emotion; they were about revealing the inherent, complex duality at the heart of being human.

The use of masks, known as prosopon in ancient Greek, was far more than a mere theatrical prop; it was a profound ritualistic device central to the Dionysiac festivals. These elaborate festivals, such as the renowned City Dionysia in Athens, were not just entertainment but deeply ingrained civic and religious events where the entire community participated in a shared spiritual experience.

The Power and Purpose of the Mask

The mask served multiple critical functions:

- Dramatic Utility: Masks allowed a small cast of actors to portray numerous characters, including women’s roles (as only men were permitted on stage). Their exaggerated features and expressions also ensured that emotions and character types were clearly visible to large audiences seated in vast open-air amphitheatres.

- Symbolic Transformation: Donning a mask was an act of profound metamorphosis. The actor shed their individual identity to embody a character, blurring the lines between the human and the divine, the performer and the persona. This was a literal manifestation of role-playing, allowing for an exploration of diverse human experiences and mythological figures.

- Ritualistic Significance: The mask imbued the performance with a sacred quality. It allowed the actor to step into a liminal space, becoming a vessel for the story and its underlying truths. This ritualistic aspect underscored the festival’s blend of religious devotion and artistic expression, where theatre itself was a form of worship.

Dionysus: God of Ecstasy and Illusion

Dionysus, as the patron god of theatre, embodied concepts that resonated deeply with the theatrical experience. He was the god of:

- Wine and Ecstasy: His domain encompassed the intoxicating liberation of the senses, the shedding of inhibitions, and the communal frenzy (maenadic rage) that could lead to both divine inspiration and madness. Theatre, with its capacity to transport audiences and performers into another reality, offered a structured, communal form of this ecstasy.

- Shapeshifting and Disguise: Dionysus himself was a master of transformation, appearing in various guises throughout myths. This divine attribute mirrored the actor’s ability to transform through costume and mask, and the play’s capacity to transform the audience’s understanding or emotional state.

- Breaking Boundaries: Dionysus frequently challenged societal norms, gender roles, and the very fabric of reality. Theatre, under his patronage, became a safe space to explore these boundaries, to question morality, and to delve into the complexities of fate and human nature without direct consequence in the real world.

Ultimately, the Dionysiac festivals, with their masked performers and compelling narratives, were powerful expressions of the god’s influence. They celebrated the human capacity for transformation—both individual and collective—and acknowledged the profound insights gained through the art of role-playing, where temporary illusion could reveal eternal truths.

Sacred Drama

Religious dramas reenacted myths about Dionysus and other deities. These performances served both entertainment and educational purposes within Greek society. Audiences learned moral lessons while honoring their gods through artistic appreciation.

The very fabric of ancient Greek performance spaces was imbued with the spirit of Dionysus, visually proclaiming the god’s dominion over dramatic arts. This wasn’t merely decorative; it was a profound statement of purpose, embedding the theatrical experience within a sacred framework.

The Visual Language of Dionysus in Theater Design

Ancient Greek theaters were not just venues; they were consecrated spaces, with their architecture often serving as a canvas for Dionysiac iconography. These visual cues reminded audiences of the god’s pervasive influence:

- Grape Vines and Ivy: Ubiquitous symbols of Dionysus, representing wine, revelry, fertility, and his connection to nature. These motifs adorned friezes, columns, and even stage backdrops, weaving a natural, yet divine, tapestry around the performers.

- Theater Masks: Beyond their practical use in character portrayal, masks themselves were deeply symbolic. They represented the transformative power of Dionysus – the ability to shed one’s identity and embody another, blurring the lines between human and divine, reality and illusion. Tragic and comic masks, often depicted in relief, were a direct homage to the dual nature of Dionysian drama.

- Thyrsi and Maenads: The thyrsus, a staff topped with a pinecone and entwined with ivy, was the emblematic implement of Dionysus and his followers, the ecstatic Maenads. Depictions of these figures in frenzied dance or procession reinforced the themes of ecstasy, liberation, and divine madness inherent in Dionysian worship and, by extension, in dramatic performance.

- Satyrs and Panthers: Mythical companions of Dionysus, satyrs embodied primal urges and revelry, while panthers or leopards symbolized his wild, untamed nature. Their presence in architectural details hinted at the raw, visceral power that drama could unleash.

These elements were not random embellishments; they were deliberate choices that transformed the physical structure into a sacred precinct, constantly affirming the theater’s dedication to the god.

Sacred Proximity: Temples and Theaters Intertwined

The architectural layout of many Greek cities further solidified the bond between Dionysus and drama. It was common practice for temples dedicated to the god to stand in immediate proximity to, or even within the same precinct as, major performance spaces.

- The Quintessential Example: The most famous instance is the Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus on the south slope of the Acropolis in Athens. Directly adjacent to it stood the Temple of Dionysus Eleuthereus. This wasn’t just convenient; it was deliberate design, creating a unified sacred complex.

- Shared Precincts: In many cases, the theater was considered an extension of the temple’s sacred ground. Processions honoring Dionysus would often begin at his temple and culminate in the theater, where his statue might even be brought into the orchestra to “witness” the plays.

- The Thymele: At the very center of the orchestra – the circular performance area – an altar known as the thymele was often placed. This altar was dedicated to Dionysus, signifying that every performance was, at its heart, an offering and a ritual act of worship directed to the god.

This physical merging of temple and theater underscored that dramatic festivals, such as the grand City Dionysia, were not mere entertainment but profound religious events, integral to the civic and spiritual life of the polis.

Drama as Divine Ritual: The Sacred Core of Performance

The deliberate integration of Dionysiac symbols and the close proximity of temples to theaters powerfully emphasized the sacred nature of dramatic arts. Drama was understood as a conduit to the divine, a means through which human beings could explore profound truths about their existence, their fate, and their relationship with the gods.

- A Form of Worship: Plays were essentially liturgical performances, offerings presented to Dionysus. The catharsis experienced by the audience – the purging of emotions like pity and fear – was not just psychological relief but a spiritual purification, a form of communion with the divine.

- The God’s Presence: The belief was that Dionysus was not just honored, but truly present in the theater during performances. Actors, through their masks and transformations, were seen as temporary vessels or conduits for divine energy, embodying archetypal figures and exploring universal human dilemmas under the god’s watchful eye.

- Exploring Existential Questions: Greek tragedy, in particular, delved into themes of hubris, fate, justice, and the often-unfathomable will of the gods. These were not secular debates but sacred inquiries, performed in a sacred space, for a sacred purpose.

Thus, the architectural and symbolic choices surrounding ancient Greek theaters were far from arbitrary. They meticulously crafted an environment where the act of performance transcended mere spectacle, becoming a profound ritual dedicated to the god of ecstasy, transformation, and divine revelation.

Wine and Transformation Symbolism

Wine represented Dionysus’s most fundamental gift to humanity. This divine beverage symbolized transformation, inspiration, and spiritual transcendence. Ancient Greeks viewed wine consumption as communion with their god.

The Sacred Transformation: Wine as Divine Metaphor

The ancient Greeks recognized an extraordinary spiritual dimension within their winemaking traditions, seeing each step of production as a sacred reenactment of cosmic cycles. This wasn’t merely agricultural work—it was participation in divine mystery.

The Cycle of Sacrifice and Renewal

The grape’s journey from vine to vessel embodied profound theological concepts:

- The Crushing Phase: Fresh grapes were literally destroyed, their skins broken and juice extracted—a violent yet necessary death

- The Fermentation Mystery: In dark vessels, the grape juice underwent an invisible transformation, bubbling with what seemed like divine breath

- The Resurrection: What emerged was something entirely new—wine possessed powers the original fruit never held

Dionysus: The Twice-Born God

This agricultural process gained deeper meaning through Dionysiac theology. According to myth, Dionysus himself experienced multiple deaths and rebirths:

- First Death: Torn apart by Titans while still a child

- Divine Intervention: Zeus rescued his heart and replanted it

- Second Birth: Emerged from Zeus’s thigh, fully divine

Each vintage thus became a ritual remembrance of the god’s own suffering and triumph over death.

Wine’s Transformative Power

The Greeks understood that wine possessed qualities that transcended mere intoxication:

- Consciousness Alteration: Wine dissolved social barriers and revealed hidden truths

- Prophetic Properties: Priestesses often consumed wine before delivering oracles

- Community Building: Symposiums centered around wine created bonds between participants

- Spiritual Liberation: The drink freed worshippers from everyday constraints, allowing divine communion

Sacred Timing and Seasonal Worship

The vintage calendar aligned perfectly with Dionysiac festivals. Harvest season coincided with the god’s major celebrations, when communities would:

- Gather to witness the first grape crushing

- Perform ritual dances mimicking the fermentation process

- Share the previous year’s wine while blessing the new harvest

- Tell stories of transformation and renewal

This cyclical worship reinforced wine’s role as liquid theology—a substance that made abstract concepts of death and rebirth tangible and experiential for ordinary believers.

The Visual Legacy of Dionysus in Ancient Art

Ancient artists developed a rich visual vocabulary to represent Dionysus’s dominion over wine, creating iconic imagery that appeared across multiple mediums and centuries.

Common Artistic Depictions

Wine Pouring Scenes

- Dionysus gracefully tilting ornate vessels, wine flowing in elegant arcs

- The god offering wine to mortals, symbolizing divine generosity

- Ceremonial libations where wine cascades onto altars or sacred ground

- Symposium scenes featuring the deity presiding over drinking parties

Sacred Wine-Making Equipment The artistic record reveals meticulous attention to viticultural tools:

- Amphorae and Storage Vessels

- Elaborately decorated ceramic jars with divine motifs

- Two-handled storage containers bearing Dionysiac symbols

- Wine cups (kylixes) adorned with grapevine patterns

- Pressing and Processing Equipment

- Stone wine presses operated by satyrs and maenads

- Wooden treading vats filled with purple-stained grapes

- Filtering equipment and fermentation vessels

- Harvesting Tools

- Curved pruning knives held by divine attendants

- Woven baskets overflowing with ripe grape clusters

- Collection vessels carried by mythological figures

Artistic Mediums and Settings

Pottery and Ceramics

- Red-figure and black-figure vase paintings dominated Greek artistic expression

- Drinking vessels ironically decorated with scenes of divine wine production

- Ceremonial kraters used for mixing wine and water

Architectural Elements

- Temple friezes showcasing elaborate harvest festivals

- Mosaic floors in Roman villas depicting Dionysiac wine miracles

- Sculptural reliefs on sarcophagi celebrating eternal feasting

Symbolic Significance in Art

These artistic representations served multiple purposes beyond mere decoration:

- Religious Education: Teaching viewers about proper wine rituals and divine favor

- Cultural Identity: Reinforcing the importance of viticulture in Mediterranean society

- Spiritual Connection: Creating visual bridges between mortal wine-making and divine blessing

- Social Status: Demonstrating wealth and sophistication through wine-related imagery

The consistent appearance of these motifs across centuries demonstrates how deeply Dionysus’s viticultural mastery resonated with ancient audiences, transforming everyday wine-making into sacred artistic expression.

Sacred Intoxication

Controlled intoxication played important roles in Dionysiac religious practices. Worshippers believed wine consumption could induce divine visions and spiritual insights. However, excess consumption led to dangerous loss of self-control.

Sacred Wine Protocols: The Art of Divine Communion

The ceremonial consumption of wine in Dionysiac rituals represented far more than simple intoxication—it was a carefully orchestrated spiritual practice that required precise adherence to ancient protocols.

The Sacred Mixing Ritual

Krasis, the ritual blending of wine and water, served as the foundation of proper Dionysiac worship:

- Traditional ratios typically ranged from 1:3 to 1:5 (wine to water)

- Special mixing vessels called kraters were blessed before each ceremony

- Designated priests or ritual leaders oversaw the mixing process to ensure purity

- The water itself was often sourced from sacred springs or purified through specific rites

Ceremonial Consumption Guidelines

Participants followed strict protocols during the drinking ceremonies:

- Libation first: A portion was always poured out as an offering to Dionysus

- Communal sharing: Wine passed from person to person in designated order

- Prescribed timing: Consumption aligned with specific ritual phases and seasonal celebrations

- Sacred vessels only: Special cups and goblets reserved exclusively for religious use

The Balance of Ecstasy and Order

This careful approach to ritual intoxication achieved a delicate equilibrium between spiritual goals and community welfare:

Spiritual Benefits:

- Facilitated divine communion and mystical experiences

- Enabled participants to access altered states of consciousness

- Created shared religious experiences that bonded communities

Social Safeguards:

- Diluted wine prevented dangerous levels of intoxication

- Structured ceremonies maintained order and prevented chaos

- Community oversight ensured responsible participation

- Ritual boundaries distinguished sacred drinking from mere revelry

Seasonal and Festival Variations

Different Dionysiac celebrations required specific wine protocols:

- Anthesteria: New wine was blessed and tasted for the first time

- Rural Dionysia: Agricultural communities celebrated with locally produced wines

- Mystery initiations: Special vintage wines were reserved for the most sacred rites

Regional Variations and Cultural Adaptations

Dionysiac symbols evolved as Greek culture spread throughout the Mediterranean world. Local traditions influenced how different communities depicted and honored the wine god. These variations enriched the overall iconographic tradition.

Roman adaptations of Dionysiac imagery reflected their cultural values and artistic preferences. Bacchus, the Roman equivalent, maintained core symbolic elements while acquiring distinctly Roman characteristics. This evolution demonstrated the god’s adaptability across cultures.

Eastern influences shaped certain aspects of Dionysiac iconography, particularly exotic animal companions and elaborate costume elements. These additions reflected stories about the god’s travels and conquests in distant lands.

Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological Evidence of Dionysiac Worship Across Ancient Civilizations

Regional Variations in Sacred Artifacts

Archaeological discoveries from Mediterranean excavation sites paint a fascinating picture of how different cultures embraced and adapted Dionysiac symbolism:

Greek Mainland Findings:

- Classical Athenian pottery featuring detailed symposium scenes with wine cups and ivy wreaths

- Marble reliefs from Delphi showing satyrs and maenads in ecstatic dance poses

- Theater masks carved into temple facades, representing Dionysus’s dual role as god of wine and drama

Roman Provincial Adaptations:

- Mosaic floors in Pompeii villas depicting Bacchanalian feasts with local Roman foods alongside traditional grapes

- Sarcophagi decorated with vine motifs but incorporating Roman imperial symbols

- Wall frescoes blending Dionysiac themes with Roman household deities

Eastern Mediterranean Interpretations:

- Syrian pottery showing Dionysus alongside local fertility goddesses

- Egyptian papyrus scrolls featuring hybrid imagery of Dionysus-Osiris worship

- Anatolian coins bearing grape clusters combined with regional dynastic emblems

Architectural Innovation Meets Sacred Tradition

Ancient builders demonstrated remarkable creativity while honoring core Dionysiac principles:

- Temple Design Adaptations

- Circular temples in Asia Minor reflecting local architectural preferences

- Underground chambers in Rome designed for mystery cult initiations

- Open-air sanctuaries in Sicily maximizing natural vineyard settings

- Decorative Element Evolution

- Corinthian capitals enhanced with grape leaf patterns instead of traditional acanthus

- Doorway lintels carved with panther motifs adapted to local stone types

- Courtyard fountains designed as wine-pouring vessels

Universal Symbolic Language

Despite these regional flourishes, certain sacred elements transcended cultural boundaries:

- The thyrsus staff – found in identical form from Spain to Syria

- Grape vine spirals – maintaining consistent clockwise direction across all cultures

- Panther companions – depicted with similar protective stances regardless of local artistic styles

- Ivy crown imagery – preserved in exact leaf-count traditions from Greece to Gaul

This archaeological evidence reveals how ancient peoples balanced cultural identity with religious authenticity, creating a rich tapestry of worship that honored both local customs and universal divine symbolism.

The pervasive influence of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, ritual madness, ecstasy, and theater, is strikingly evident in the vast array of archaeological finds housed in museums globally. These collections are not merely repositories of ancient objects; they are dynamic archives that continually inform and reshape our understanding of classical antiquity.

A Kaleidoscope of Dionysiac Artistry

From the sun-drenched shores of the Mediterranean to the far-flung outposts of the Roman Empire, countless artifacts bear witness to Dionysus’s enduring appeal. This iconography manifests across an astonishing range of mediums, each offering a unique lens into ancient life:

- Pottery and Vases: Exquisitely painted kraters, amphorae, and kylixes depict Dionysus and his boisterous retinue—maenads in ecstatic dance, satyrs in various states of revelry, and Silenus, his wise and often inebriated companion. These scenes illuminate aspects of symposia (drinking parties), cult rituals, and mythological narratives.

- Sculptures and Statuettes: Marble and bronze figures, ranging from monumental cult statues to intimate household shrines, capture the god’s youthful vigor, often adorned with his signature attributes: the thyrsus (a fennel-stalk staff topped with ivy and a pinecone), a kantharos (drinking cup), and garlands of ivy or grapevine.

- Mosaics and Frescoes: Elaborate floor mosaics and vibrant wall paintings found in villas across the Roman world frequently feature Dionysiac themes. These could range from grand processional scenes to intimate portraits, decorating spaces where wine and revelry were central to daily life.

- Sarcophagi: The presence of Dionysiac imagery on Roman sarcophagi suggests a profound connection to beliefs about the afterlife, resurrection, and the promise of a joyful existence beyond death, mirroring the god’s own journey through death and rebirth.

- Coins, Jewelry, and Personal Adornments: Even everyday items and luxury goods bore symbols of Dionysus, indicating his widespread veneration and the integration of his cult into both public and private spheres.

Unlocking Ancient Religious Practices and Beliefs

These artifacts serve as primary documents, allowing scholars to reconstruct the multifaceted nature of Dionysiac worship and its impact on ancient society:

- Ecstatic Cults and Mystery Rites: Depictions of maenads in frenzied dances, often holding snakes or tearing apart sacrificial animals, provide visual evidence of the god’s ecstatic cults. These rituals offered a pathway to divine possession and a temporary escape from societal constraints, particularly for women.

- Symposia and Social Rituals: The ubiquitous presence of Dionysus on drinking vessels underscores his central role in the symposium, a male-dominated social gathering where wine, poetry, music, and philosophical discussion intertwined. These scenes reveal the ritualistic consumption of wine and its significance in fostering communal bonds.

- Theatrical Origins: As the patron god of theater, Dionysus is often depicted with masks, dramatic scenes, and choruses. These images offer crucial clues to the evolution of Greek drama, from its ritualistic origins to the grand festivals like the Dionysia in Athens.

- Death and Rebirth Symbolism: The recurring motif of Dionysus’s triumph over death, his association with vegetation cycles, and his presence on funerary monuments highlight his role as a chthonic deity promising rebirth and eternal bliss to his initiates.

Tracing Artistic Traditions and Regional Interpretations

The evolution of Dionysiac iconography also provides a rich tapestry for understanding ancient artistic traditions:

- Stylistic Development: Scholars can trace the stylistic shifts in Greek and Roman art through Dionysiac representations, observing changes from the rigid forms of the Archaic period to the dynamic realism of the Hellenistic era, and subsequent Roman interpretations and adaptations.

- Medium-Specific Techniques: The way Dionysus is rendered in different materials—the fluidity of paint on a vase, the solidity of marble, the intricate detail of a mosaic—showcases the diverse technical skills and aesthetic choices of ancient artisans.

- Cross-Cultural Diffusion: The spread of Dionysiac imagery across the Mediterranean and beyond reveals the dynamic interplay of cultural exchange. Roman artists, for instance, often reinterpreted Greek prototypes, adapting them to their own aesthetic preferences and religious contexts.

The Ongoing Quest: New Discoveries and Scholarly Insights

The narrative surrounding Dionysus is far from complete. Archaeological excavations continually unearth new treasures, from previously unknown cult sites to spectacular artistic commissions. Recent discoveries, such as:

- Intact Roman Villas: Providing comprehensive decorative schemes that illuminate the function and symbolism of Dionysiac art within specific architectural contexts.

- Shipwrecks: Yielding previously submerged cargo, including sculptures and luxury goods that expand our knowledge of trade routes and artistic dissemination.

- Digital Reconstructions: Utilizing advanced technology to virtually restore damaged artifacts or reconstruct entire ancient spaces, offering fresh perspectives on how these objects were originally experienced.

Moreover, contemporary scholarship employs interdisciplinary approaches, integrating art history, archaeology, classical philology, and religious studies to re-examine existing collections with fresh eyes. This ongoing process of discovery and reinterpretation ensures that our understanding of Dionysus—and through him, the vibrant tapestry of ancient Greek and Roman culture—continues to deepen and evolve.

Conclusion

Dionysus’s rich symbolic vocabulary reflects the complexity of ancient Greek religious thought. Each attribute—from the thyrsus staff to leopard companions—carried multiple layers of meaning that resonated with ancient worshippers. These symbols connected the divine realm to human experience through powerful visual metaphors.

Delving into the rich tapestry of Dionysiac iconography offers an unparalleled journey into the very heart of ancient Greek civilization. Far more than mere decorative motifs, these symbols served as profound cultural touchstones, reflecting the Greeks’ intricate worldview, their spiritual practices, and their sophisticated artistic sensibilities.

Unveiling Ancient Greece Through Dionysiac Symbols

1. A Window into Ancient Greek Culture: Dionysus’s symbols provide direct insights into the daily lives, social structures, and values of the ancient Greeks.

- Social Rituals: The kantharos (a deep, two-handled drinking cup) immediately evokes the symposium, the all-male drinking parties central to Greek social and intellectual life. Here, wine fostered philosophical debate, poetic recitation, and communal bonding.

- Theatrical Genesis: The mask, a quintessential Dionysian emblem, is intrinsically linked to the birth of Greek tragedy and comedy. It represents not only the god’s transformative power but also the fundamental role of theater in Greek society – a civic and religious event designed to explore human nature and destiny.

- Rural Life & Festivals: Symbols like ivy, grapevines, and figs connect Dionysus to the agricultural cycles and the rural festivals that punctuated the Greek year, celebrating fertility, harvest, and the wild abundance of nature.

2. Deepening Religious Understanding: The iconography illuminates the unique and often paradoxical nature of Dionysian worship, which stood apart from the Olympian pantheon’s more ordered rituals.

- Ecstatic Worship: The thyrsus (a staff topped with a pine cone, often entwined with ivy) symbolizes the frenzied, ecstatic rituals performed by Maenads – female followers who sought direct communion with the god through dance, music, and altered states of consciousness.

- Mystery Cults: The veiled nature of some Dionysian symbols hints at the Dionysian Mysteries, secret rites promising initiates spiritual purification, a better afterlife, and a profound connection to the divine life force, often involving symbolic death and rebirth.

- Divine Presence: The depiction of panthers or leopards accompanying Dionysus signifies his wild, untamed, and exotic nature, emphasizing his arrival from the East and his association with primal, elemental forces.

3. Artistic Expression and Innovation: Dionysian themes were a fertile ground for ancient Greek artists, inspiring creativity across various mediums.

- Vase Painting: Scenes of Dionysus, his satyrs, and maenads reveling were incredibly popular on attic pottery, showcasing intricate narratives, dynamic compositions, and the evolving styles of black-figure and red-figure techniques.

- Sculpture & Reliefs: From monumental cult statues to intricate temple friezes, Dionysian imagery allowed sculptors to explore movement, emotion, and the human form in states of ecstatic abandon, often contrasting with the serene idealism of other Olympian deities.

- Mosaics & Frescoes: In villas and public spaces, Dionysian motifs brought vibrant life and a sense of festivity, decorating floors and walls with scenes of banquets, dances, and mythological narratives.

Dionysus’s Enduring Echoes in Modernity

The captivating power of Dionysus’s symbols transcends antiquity, permeating contemporary consciousness in diverse and fascinating ways.

- Modern Art & Performance: Artists continue to draw inspiration from Dionysian themes of liberation, chaos, and transformation.

- Visual Arts: From Picasso’s exploration of primal forces to contemporary performance art that challenges societal norms, the spirit of Dionysus endures.

- Fashion: Designers often incorporate elements of wildness, theatricality, and opulent revelry reminiscent of Dionysian processions.

- Literary & Philosophical Resonance:

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s seminal work, The Birth of Tragedy, posited Dionysus as the embodiment of primal chaos, emotion, and instinct, contrasting him with the Apollonian principle of order and reason. This dichotomy profoundly influenced 20th-century thought.

- Carl Jung recognized Dionysus as an archetypal figure representing the collective unconscious’s wild, transformative energies.

- Contemporary Literature: Authors frequently explore themes of altered states, societal rebellion, and the search for authentic experience, echoing Dionysian narratives.

- Popular Culture’s Embrace:

- Film & Television: From portrayals of hedonistic parties to narratives of identity transformation and the exploration of psychological depths, Dionysian influence is palpable.

- Music & Festivals: The communal euphoria of music festivals, rave culture, and even rock concerts often mirrors the ecstatic release sought in ancient Dionysian rites.

- Counter-Culture Movements: The desire to break free from societal constraints, embrace individuality, and celebrate alternative lifestyles frequently aligns with the Dionysian spirit of rebellion and liberation.

The Universal Allure: Transformation, Celebration, and Transcendence

The timeless appeal of Dionysus and his iconography lies in their resonance with fundamental human desires and experiences. These aren’t just ancient concepts; they are deeply ingrained aspects of the human condition.

- The Call of Transformation:

- Personal Metamorphosis: Dionysus is the god of masks and disguise, symbolizing the human capacity for change, self-reinvention, and the shedding of old identities to embrace new ones.

- Life Cycles: His mythology, particularly his death and rebirth, speaks to the universal understanding of cyclical patterns in nature and human life – growth, decay, and renewal.

- Breaking Boundaries: He represents the urge to transcend conventional limits, whether social, psychological, or spiritual, encouraging us to explore the uncharted territories of self and society.

- The Spirit of Celebration:

- Joyful Liberation: Dionysus embodies the uninhibited joy of revelry, the release of tension through dance, music, and communal festivity. This speaks to our innate need for moments of collective happiness and freedom from daily anxieties.

- Embracing Excess: He validates the human desire for indulgence and pleasure, reminding us that life is also about embracing the richness of sensory experience.

- Communal Bonding: His festivals fostered a sense of unity and shared experience, echoing our enduring need for belonging and collective expression.

- The Quest for Spiritual Transcendence:

- Ecstatic Experience: Dionysus offers a pathway to altered states of consciousness, where the boundaries between self and other, human and divine, seem to dissolve. This resonates with humanity’s long-standing search for deeper meaning and mystical encounters.

- Connection to the Divine: Through intoxication and ecstatic ritual, his followers sought direct, visceral communion with the divine, a primal yearning for spiritual connection that persists across cultures and eras.

- Beyond the Mundane: The allure of Dionysus lies in his promise of a reality beyond the ordinary, a realm where instincts, intuition, and the subconscious hold sway, offering a powerful counterpoint to the rational and predictable.

In essence, Dionysus’s symbols are not merely relics of the past; they are enduring archetypes that continue to illuminate the depths of the human psyche, reflecting our eternal fascination with the wild, the joyful, and the profoundly transformative aspects of existence.

Contemporary scholars and artists still find inspiration in these ancient symbols. They represent timeless themes of creativity, fertility, and the tension between civilization and wild nature. Through studying Dionysiac iconography, we gain deeper appreciation for both ancient wisdom and enduring human concerns.