Far from a simple deity, Dionysus stands as a profound paradox, a god whose very essence challenged the ordered world of the Olympians and the rational thought prized by Greek philosophy. His compelling allure stemmed from his embodiment of life’s most potent, often contradictory, forces.

The Duality: Divine Ecstasy vs. Terrifying Madness

Dionysus was the ultimate representation of liminality, thriving on the boundaries between civilization and wilderness, sanity and frenzy. This is most vividly illustrated in his dual nature:

- Divine Ecstasy (The Liberating Force):

- This aspect brought profound joy, spiritual liberation, and a sense of unity with the divine and nature.

- Rituals and Revelry: His followers, particularly the female Maenads and the male Satyrs, engaged in ecstatic dances, music (flutes, drums, cymbals), and feasting in wild, untamed landscapes.

- Transcendence: Through these rites, mortals could temporarily shed their mundane identities, social constraints, and anxieties, experiencing a heightened state of being – a true enthusiasmos (being filled with the god). It was a profound release, often leading to a feeling of spiritual enlightenment and uninhibited freedom.

- Inspiration: This divine intoxication could also inspire artistic creativity, prophecy, and a deeper understanding of the world.

- Terrifying Madness (The Destructive Force):

- The flip side of ecstasy was a terrifying, uncontrollable frenzy that obliterated reason and could lead to brutal violence.

- Loss of Control: When the boundaries blurred too much, the liberating abandon could devolve into delusion, savagery, and a complete loss of self.

- Violent Outbursts: Tales abound of Maenads, driven to madness by the god, tearing apart wild animals – and sometimes even humans – in acts of sparagmos (ritual dismemberment), consuming raw flesh. The mythical king Pentheus of Thebes met a gruesome end at the hands of his own mother and aunts, who, maddened by Dionysus, mistook him for a wild beast.

- Chaos: This destructive potential highlighted the inherent danger of unchecked passion and the fragility of human reason when confronted with overwhelming primal forces.

Domains of Profound Influence

Dionysus’s sway extended over fundamental aspects of ancient Greek life, each colored by his complex nature:

- Wine: The Catalyst for Transformation

- More than just a beverage, wine was seen as a divine gift, a transformative elixir capable of altering perception.

- Social Lubricant: It facilitated social gatherings, loosening inhibitions, and fostering camaraderie.

- Ritual Element: Central to many religious rites, it was used for libations and as a means to induce altered states of consciousness, allowing mortals to connect with the divine.

- Double-Edged Sword: While it could inspire joy and creativity, excessive consumption led to intoxication, folly, and destructive behavior – mirroring the god’s own duality.

- Fertility: Life’s Abundance and Renewal

- Dionysus was intrinsically linked to the teeming life force of nature, particularly the vine, but also to the broader cycles of growth, decay, and rebirth.

- Agricultural Bounty: His cult ensured the fertility of crops, livestock, and the general abundance of the earth.

- Procreation: He was associated with human fertility and the generative power of life, often represented by phallic symbols in his processions.

- Seasonal Cycles: His myths often reflect the annual death and rebirth of the vine, symbolizing the continuous renewal of life.

- Theater: The Mirror of Human Experience

- As the patron god of drama, particularly tragedy, Dionysus presided over the very art form that allowed Greeks to explore the depths of human emotion and fate.

- The Mask: The theatrical mask, central to ancient Greek drama, perfectly encapsulated Dionysus’s themes of identity, transformation, and the revelation of hidden truths. It allowed actors to embody roles, transcending their own selves, much like his worshippers transcended their daily lives.

- Catharsis: The experience of watching a play, especially a tragedy, could evoke a powerful emotional release (catharsis) in the audience, mirroring the emotional intensity of Dionysian rituals.

- Festivals: Major dramatic festivals, like the City Dionysia in Athens, were held in his honor, underscoring his vital connection to artistic expression and communal experience.

- Wild Abandon: Breaking the Bonds of Convention

- This overarching theme weaves through all his domains, representing the urge to break free from societal norms, rational thought, and self-control.

- Liberation: It offered an escape from the mundane, the opportunity for self-discovery, and a profound connection to primal forces.

- Destruction: Yet, this same abandon, when uncontrolled, threatened the very fabric of society, leading to chaos, violence, and the dissolution of identity.

In essence, Dionysus was the god who dared humanity to confront its own wildness, to embrace the powerful, often terrifying, forces that lie beneath the surface of civilization, offering both profound liberation and the potential for devastating self-destruction.

Unlike other Olympian gods who maintained consistent divine personas, Dionysus represented duality itself. He brought joy through wine and celebration, yet simultaneously unleashed chaos through ritual frenzy. Furthermore, his influence extended far beyond simple intoxication, encompassing the creative arts, agricultural fertility, and the thin boundary between civilization and wilderness.

The Extraordinary Birth of Dionysus

The Divine Deception That Changed Everything

The relationship between Zeus and Semele began like many of the king of gods’ mortal affairs – with passion and secrecy. Semele, daughter of King Cadmus of Thebes, possessed a beauty that captivated even the most powerful deity in the Greek pantheon. Their clandestine meetings were filled with tender moments, but Zeus appeared to her in human form, concealing his true divine nature.

Hera’s Masterful Revenge Plot

Hera’s discovery of this affair ignited a fury that would become legendary even by her standards. Rather than direct her wrath immediately at Zeus – a confrontation she knew would be futile – the queen of gods devised a far more insidious plan:

- The disguise: Hera transformed herself into Beroe, Semele’s trusted elderly nurse

- The manipulation: She spent weeks gaining Semele’s confidence, listening to her romantic tales

- The deadly suggestion: Hera planted seeds of doubt about her lover’s identity

- The fatal request: She convinced Semele to ask Zeus to appear before her in his true form

The Tragic Consequences of Divine Truth

When Semele, now pregnant with Zeus’s child, made her fateful request, she unknowingly sealed her doom. Zeus had sworn by the River Styx – an unbreakable oath among the gods – to grant her any wish. The consequences were catastrophic:

- Zeus’s true form revealed: Thunder, lightning, and divine fire

- Mortal flesh cannot withstand divinity: Semele was instantly incinerated

- The unborn child’s peril: The fetus faced certain death in the flames

- Zeus’s desperate intervention: The king of gods performed an unprecedented rescue

This moment would forever distinguish Dionysus from his divine siblings, as he became the god “twice-born” – first from his mortal mother’s womb, and then from Zeus’s own thigh, where he completed his gestation protected by divine flesh.

The jealous queen of the gods disguised herself as an old woman and convinced Semele to ask Zeus to appear before her in his true form. Consequently, when Zeus revealed himself with his lightning and thunder, the mortal woman was instantly killed by his divine radiance. Nevertheless, Zeus managed to save the unborn child from Semele’s womb.

In an extraordinary act of divine preservation, Zeus sewed the infant into his own thigh. Therefore, Dionysus completed his gestation within his father’s body, earning him the epithet “twice-born.” This unusual birth story established Dionysus as a god who bridged the mortal and divine realms, a theme that would define his entire mythology.

Domains and Divine Powers

Dionysus governed multiple interconnected spheres of influence that reflected humanity’s complex relationship with pleasure, creativity, and loss of control. His primary domain encompassed viticulture and winemaking, making him essential to both agriculture and social customs.

Wine and Intoxication

As the god of wine, Dionysus controlled both the beneficial and destructive aspects of intoxication. Wine brought people together in celebration, loosened social constraints, and inspired artistic creativity. Additionally, it served religious purposes in various rituals and ceremonies throughout the Greek world.

However, Dionysus also represented wine’s darker potential. Excessive consumption led to violence, poor judgment, and social chaos. Thus, the god embodied the delicate balance between civilized enjoyment and dangerous excess.

Fertility and Agriculture

Beyond his iconic association with viticulture, Dionysus was fundamentally intertwined with the broader concept of agricultural fertility, particularly concerning the bounty of fruit-bearing plants and trees.

- God of the Orchard and Grove: While grapes were central, Dionysus’s domain extended to virtually every fruit and nut tree vital to the ancient Greek diet and economy. This included:

- Olives: A sacred tree, providing oil for food, light, and anointing.

- Figs: A staple food, often dried for year-round sustenance.

- Pomegranates: Rich in seeds, symbolizing fertility and abundance.

- Apples, Pears, Almonds: Contributing to a diverse and lush agricultural landscape.

- He governed the entire life cycle of these plants – from the initial budding and blossoming in spring to the plump, ripe harvest of autumn. His presence ensured not just the quantity, but also the sweetness, juiciness, and intoxicating quality that made these fruits so prized.

Farmers across Greece deeply understood their dependence on the god’s favor, honoring him with seasonal reverence.

- Honoring the Life-Giver Through Seasons: Throughout the agricultural calendar, specific rituals and festivals acknowledged Dionysus’s critical role:

- Spring (Planting Season): As new life emerged from the earth, farmers offered prayers and libations – often milk, honey, or unfermented grape juice – to invoke his blessing for robust growth and a bountiful yield. Festivals like the Anthesteria, while celebrating new wine, also marked a broader welcome to spring’s generative power and the reawakening of the earth.

- Autumn (Harvest Season): This was a period of joyous thanksgiving. Beyond the grape harvest, farmers celebrated the collection of all tree-borne fruits. Festivals such as the Rural Dionysia involved elaborate processions, songs, and dramatic performances, serving both as an expression of gratitude and a plea for continued benevolence in future seasons. These were not solitary acts but vibrant communal events, fostering solidarity and a deep connection to the rhythms of nature.

Moreover, Dionysus’s connection to fertility extended profoundly to human reproduction and the vital continuation of family lines.

- The Procreative Force: In a society where the perpetuation of the oikos (household/family) and the birth of heirs were paramount, Dionysus’s influence was subtle yet powerful. He embodied the raw, untamed life force essential for procreation.

- Phallic Symbolism: This connection was overtly expressed through the widespread use of phallic symbols in Dionysian rites and imagery. The phallus represented male potency and the primal, irresistible urge to create. Processions often featured large phallic effigies, openly celebrating this generative power.

- Ensuring Offspring: While Hera presided over marriage, Dionysus contributed to the fruitfulness of the union, ensuring the successful conception and birth of children. His energy was believed to fuel the very act of creation, making him a silent patron for couples hoping to expand their family.

- Wild, Ecstatic Fertility: Unlike the more ordered fertility of Demeter (who governed grains), Dionysus’s fertility was often seen as more primal, ecstatic, and overflowing – a potent, irresistible urge that drove both nature and humanity to reproduce and thrive. His worship tapped into this fundamental, life-affirming energy, celebrating the very essence of existence and legacy.

Theater and Artistic Expression

Dionysus became closely associated with dramatic arts, particularly tragedy and comedy. The annual Dionysia festivals in Athens featured theatrical competitions that produced many of Greece’s greatest plays. Furthermore, actors and playwrights considered him their patron deity, seeking his blessing for successful performances.

The God’s Mythological Journeys

After reaching adulthood, Dionysus embarked on extensive travels throughout the known world, spreading knowledge of viticulture and establishing his religious cult. These journeys demonstrated his role as a civilizing force, despite his association with wild behavior.

His travels took him through Asia Minor, India, and various Greek territories. Wherever Dionysus went, he taught people how to cultivate grapes and produce wine. Consequently, communities that welcomed him prospered, while those that rejected him faced divine punishment.

One famous myth describes his encounter with pirates who attempted to kidnap him for ransom. However, Dionysus revealed his divine nature by transforming their ship’s masts into grape vines and turning the sailors into dolphins. This story illustrates both his power and his tendency toward dramatic, transformative punishments.

The Maenads: Divine Followers

Dionysus attracted devoted female followers known as maenads, whose name literally meant “mad women.” These worshippers abandoned conventional social roles to follow their god into the wilderness, where they engaged in ecstatic rituals.

Maenads wore animal skins, carried thyrsus staffs topped with pine cones, and participated in frenzied dances. During their rituals, they achieved altered states of consciousness that believers interpreted as divine possession. Additionally, they were said to possess supernatural strength and the ability to tear apart wild animals with their bare hands.

These female devotees represented the liberating aspect of Dionysiac worship, offering women temporary escape from restrictive social expectations. Nevertheless, their behavior also embodied the dangerous potential of uncontrolled religious ecstasy.

Satyrs and Divine Companions

The Wild Retinue of Dionysus

Satyrs: Nature’s Unbridled Spirits

The satyrs formed an integral part of Dionysus’s divine entourage, serving as living embodiments of humanity’s primal connection to the natural world. These fascinating creatures possessed:

- Human torsos and faces with distinctly mischievous expressions

- Goat-like legs and hooves that allowed them to navigate rough terrain with ease

- Small horns protruding from their foreheads

- Pointed ears that could detect the slightest sounds in the wilderness

- Tails that swished with their constant movement and energy

Masters of Hedonistic Pursuits

Unlike the structured worship found in other Greek religious practices, satyrs represented pure, unfiltered desire. Their daily activities included:

- Wine consumption – They were perpetually intoxicated, celebrating the gift of the vine

- Musical performances – Playing reed pipes, drums, and other rustic instruments

- Dancing – Engaging in frenzied, ecstatic movements that honored their god

- Pursuing romantic encounters – Following their impulses without social constraints

- Feasting – Indulging in the bounty of nature’s harvest

Symbols of Humanity’s Dual Nature

The half-human, half-animal composition of satyrs served as a powerful metaphor in Greek culture. They represented:

The Civilized Self vs. The Wild Self

- Their human upper bodies symbolized rational thought and social awareness

- Their goat-like lower halves embodied instinct, passion, and natural urges

- This duality reflected the eternal struggle between societal expectations and personal desires

Guardians of Sacred Mysteries

Beyond their reputation for revelry, satyrs held important spiritual significance:

- They served as intermediaries between the mortal and divine realms

- Their presence signaled the breakdown of social barriers during Dionysiac festivals

- They protected the sacred knowledge of wine-making and agricultural cycles

- Their wild nature reminded worshippers that divine ecstasy required abandoning conventional restraints

Cultural Impact and Artistic Representation

Ancient Greek artists frequently depicted satyrs in:

- Pottery paintings showing them in various stages of celebration

- Theater performances where they provided comic relief in satyr plays

- Sculpture that captured their dynamic, energetic poses

- Frescoes adorning temples and private homes dedicated to Dionysus

These artistic representations helped spread the understanding that true spiritual liberation sometimes required embracing one’s more primitive, instinctual nature.

Satyrs were known for their love of wine, music, and sexual pursuits. They played pipes and drums during Dionysiac celebrations, creating the rhythmic accompaniment for ecstatic dancing. Furthermore, their presence emphasized the god’s connection to fertility and the natural world’s reproductive forces.

The most famous satyr was Silenus, Dionysus’s elderly tutor and companion. Despite his drunken appearance, Silenus possessed great wisdom and often shared profound insights when captured and questioned by mortals.

Dionysiac Festivals and Worship

Greek communities celebrated Dionysus through various festivals that combined religious devotion with theatrical performance and communal celebration. The most famous of these was the Great Dionysia in Athens, which lasted several days and attracted visitors from throughout the Greek world.

During these festivals, participants engaged in processions, theatrical performances, and ritualized drinking. The celebrations temporarily suspended normal social hierarchies, allowing slaves and citizens to mingle freely. Moreover, the festivals provided opportunities for political commentary through satirical plays and comedic performances.

Rural communities held smaller Dionysiac celebrations called Anthesteria, which marked the opening of new wine and honored the dead. These festivals demonstrated how Dionysus’s worship permeated both urban and agricultural Greek society.

The Dual Nature of Divine Madness

Dionysus embodied the concept that madness could be both divine gift and terrible curse. His followers experienced ecstatic states that they interpreted as communion with the divine. However, those who opposed or disrespected the god faced destructive madness as punishment.

The tragic downfall of King Pentheus of Thebes serves as a chilling testament to the perils of denying Dionysus’s multifaceted divine nature. Pentheus, a young and rigidly authoritarian ruler, embodied the forces of order and rationality. He viewed Dionysus’s arrival in Thebes and the burgeoning cult of ecstatic worship not as a sacred revelation, but as a dangerous, foreign contagion threatening to corrupt the moral fabric and civic stability of his kingdom.

Here’s a deeper look into the unfolding tragedy:

**Pentheus’s Blind Resistance to the Divine**

- A King’s Hubris: Pentheus’s fatal flaw was his hubris – an arrogant overconfidence that led him to believe he could control or suppress a god. He saw the Bacchic rites, with their wild music, dancing, and wine-fueled abandon, as mere licentiousness and a threat to his authority.

- The Campaign of Suppression: His efforts to quash the burgeoning Dionysian cult were swift and severe. He ordered the imprisonment of Dionysus’s followers, including the god himself (who often appeared in human guise), and issued edicts banning the revels that had begun to draw the women of Thebes, including his own mother and aunts, to the slopes of Mount Cithaeron.

- A Clash of Ideologies: This wasn’t merely a political disagreement; it was a fundamental clash between the Apollonian ideals of order, reason, and control (which Pentheus championed) and the Dionysian embrace of chaos, ecstasy, and the primal forces of nature and the human psyche. Pentheus simply refused to acknowledge that such a powerful, untamed force could be divine.

**The God’s Calculated Vengeance**

Dionysus, ever the master of illusion and psychological manipulation, did not directly strike Pentheus down. Instead, he orchestrated a slow, terrifying unraveling:

- Ensnaring the King: Dionysus, feigning helplessness in captivity, subtly began to manipulate Pentheus. He piqued the king’s morbid curiosity about the forbidden rites, eventually persuading him to spy on the maenads, disguised as a woman, to see their “depravity” firsthand. This act of voyeurism was Pentheus’s final, fatal step into the god’s trap.

- The Mountaintop Frenzy: On Mount Cithaeron, the maenads – including Pentheus’s mother, Agave, and his aunts, Ino and Autonoë – were in the throes of mania, a state of divine madness induced by Dionysus. Empowered by the god, they possessed superhuman strength and a terrifying, unseeing zeal.

- The Revelation and the Hunt: Dionysus dramatically revealed Pentheus’s hidden presence to the frenzied women. In their Bacchic trance, they perceived him not as their king or kin, but as a wild beast – a lion or boar – that needed to be hunted and torn apart.

**The Ultimate Horror: A Mother’s Unknowing Act**

The climax of the myth is perhaps one of the most gruesome and heartbreaking in all of Greek mythology:

- The Sparagmos: The maenads, led by Agave, descended upon Pentheus. With their bare hands, they performed the ritualistic sparagmos – literally tearing him limb from limb. The king, who had sought to impose order, was utterly dismembered by the very forces he denied.

- Agave’s Tragic Triumph: His mother, Agave, was at the forefront of this horrific act. In her Dionysian frenzy, she believed she had successfully hunted a magnificent wild animal. She triumphantly impaled her son’s severed head on a thrysus (the ritual staff of Dionysus) and proudly carried it back to the city of Thebes, eager to display her “trophy” to her father, Cadmus.

- The Return to Sanity: The truly devastating moment arrives as Cadmus, horrified, slowly and gently guides his daughter back to sanity. As the divine madness recedes, the horrific truth dawns on Agave: the “lion’s head” she so proudly brandishes is, in fact, the head of her own son, Pentheus. The realization shatters her, revealing the full, brutal extent of Dionysus’s retribution.

This myth profoundly illustrates the destructive power of denial and the catastrophic consequences of refusing to acknowledge the wild, irrational, and ecstatic aspects of existence that Dionysus embodies. It’s a stark reminder that some divine forces, while capable of immense joy and liberation, also possess a terrifying capacity for vengeance when scorned.

This story demonstrates how Dionysus punished those who rejected the transformative power of religious ecstasy. Furthermore, it shows how the god’s influence could turn familial bonds into instruments of destruction.

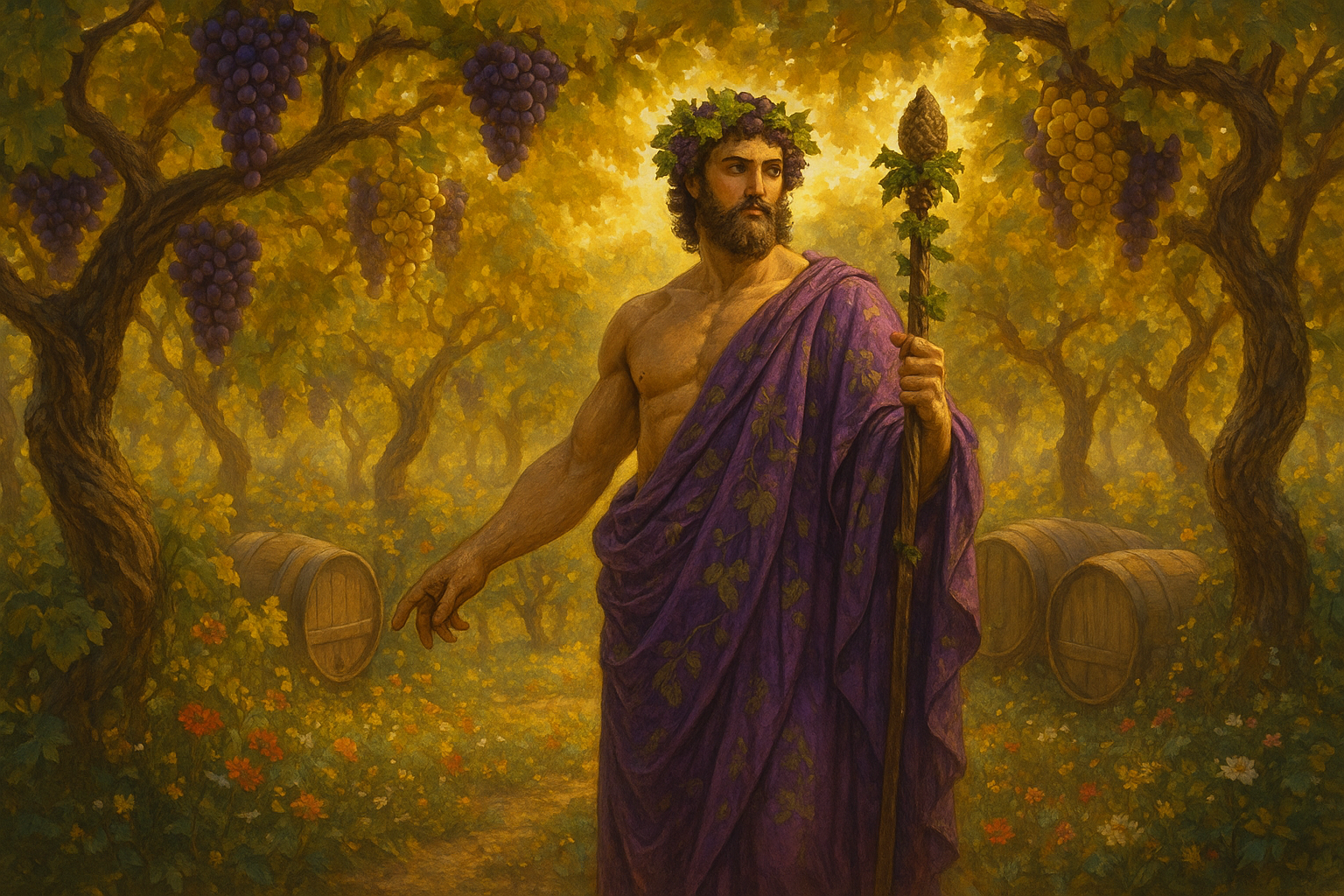

Symbols and Sacred Objects

Dionysus was associated with numerous symbols that reflected his various domains and powers. The most obvious was the grapevine, representing his connection to wine and agriculture. Ivy, which remained green throughout winter, symbolized eternal life and resurrection.

The thyrsus, a staff topped with a pine cone and wrapped in ivy, served as the primary symbol of Dionysiac worship. Followers carried these staffs during rituals and processions. Additionally, the pine cone represented fertility and regeneration, while the ivy signified the god’s power over nature.

Other important symbols included the leopard, representing wild nature and untamed power, and the theater mask, reflecting his patronage of dramatic arts. Wine cups and amphoras also served as common symbols in artistic depictions of the god.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Dionysus’s influence extended far beyond ancient Greek religion, shaping Western concepts of artistic inspiration, religious ecstasy, and the relationship between civilization and wildness. His mythology explored themes that remain relevant today: the tension between order and chaos, the power of collective celebration, and the double-edged nature of liberation.

Roman culture adopted Dionysus as Bacchus, maintaining many of his characteristics while adapting his worship to Roman sensibilities. Subsequently, Renaissance artists frequently depicted Bacchanalian scenes, drawing inspiration from ancient descriptions of Dionysiac festivals.

Modern psychology and anthropology continue to find relevance in Dionysiac themes, particularly regarding altered states of consciousness, group psychology, and the role of ritual in human society. Furthermore, his association with theater ensures his continued presence in discussions of dramatic arts and performance.

Conclusion

The Divine Paradox: Order Meets Chaos

Dionysus represents the ultimate contradiction within the Greek pantheon – simultaneously bringing both ecstatic joy and terrifying madness to mortals. Unlike the structured domains of other Olympian gods, his realm exists in the liminal spaces where:

- Civilization meets wilderness

- Sacred rituals blur with primal instincts

- Death transforms into rebirth

- Individual identity dissolves into collective experience

This duality made him both beloved and feared, as communities recognized that the same force bringing abundant harvests and celebratory festivals could just as easily unleash destructive frenzy.

The Twice-Born God: A Birth Like No Other

From Mortal Womb to Divine Thigh

The circumstances surrounding Dionysus’s entrance into the world defied conventional divine births. When Zeus’s mortal lover Semele was tricked by jealous Hera into requesting to see Zeus in his true form, the resulting lightning strike killed the pregnant princess instantly.

The rescue mission that followed became legendary:

- Zeus salvaged the unborn child from Semele’s womb

- Sewed the fetus into his own thigh for protection

- Completed the gestation period within his divine body

- Delivered Dionysus as a fully-formed god

This extraordinary birth earned him the title “twice-born” and established his unique position as both mortal and divine, making him the perfect bridge between human experience and godly power.

The Wandering God: Journeys Across Ancient Worlds

Establishing Divine Authority Through Travel

Dionysus’s extensive travels weren’t mere adventures – they represented systematic campaigns to establish his worship and demonstrate his divine authority. His journeys took him through:

Major Destinations:

- India – Where he learned mystical practices and gathered exotic followers

- Thrace – His first European conquest, establishing wine culture

- Asia Minor – Spreading mystery religions and ecstatic rituals

- Egypt – Connecting with ancient wisdom traditions

Resistance and Triumph

Each destination presented unique challenges as local rulers often viewed this foreign god with suspicion. The pattern repeated across cultures:

- Initial rejection by established authorities

- Demonstration of divine power through miracles and madness

- Conversion of the masses through wine and celebration

- Punishment of resisters with divine retribution

- Establishment of permanent worship and festivals

The Maenads: Divine Madness in Human Form

Women Transformed by Divine Ecstasy

The Maenads represented Dionysus’s most devoted and dangerous followers – women who abandoned conventional social roles to embrace divine madness. These weren’t merely enthusiastic worshippers, but transformed beings who exhibited supernatural abilities:

Physical Transformations:

- Superhuman strength capable of tearing apart wild animals

- Immunity to pain from fire, weapons, and harsh elements

- Enhanced senses that connected them to natural forces

- Prophetic abilities emerging from their altered states

Ritual Behaviors:

- Omophagia – consuming raw flesh to commune with the divine

- Sparagmos – ritual dismemberment representing death and rebirth

- Ecstatic dancing that could last for days without exhaustion

- Sacred drama reenacting mythological stories

Wine as Sacred Transformation

Beyond Simple Intoxication

Wine in Dionysiac tradition served as far more than an alcoholic beverage – it functioned as a sacred technology for consciousness transformation. The god’s gift of viticulture carried profound spiritual implications:

Symbolic Meanings:

- Death and resurrection – grapes must die to become wine

- Transformation of matter – simple fruit becomes divine nectar

- Community bonding – shared drinking creates social unity

- Temporary transcendence – escape from ordinary consciousness

- Divine communion – direct connection with godly essence

Ritual Applications:

- Religious ceremonies requiring altered states of consciousness

- Seasonal festivals celebrating agricultural cycles

- Mystery initiations revealing hidden spiritual truths

- Theatrical performances enhancing emotional and spiritual impact

Artistic Expression as Divine Channel

Theater, Music, and Creative Ecstasy

Dionysus’s influence on artistic expression fundamentally shaped Western culture. His connection to creativity wasn’t coincidental but essential – art served as a vehicle for divine revelation and community transformation.

Theatrical Innovations:

- Greek tragedy emerged from Dionysiac festivals

- Chorus and dance replicated ritual practices

- Masks and costumes enabled identity transformation

- Cathartic experiences provided spiritual cleansing for audiences

Musical Traditions:

- Rhythmic drumming induced trance states

- Flute music accompanied ecstatic dancing

- Choral singing created communal spiritual experiences

- Improvisational elements allowed divine inspiration to flow

This revolutionary approach to artistic expression established patterns that continue influencing creative traditions, where artists seek to channel forces beyond ordinary consciousness to create transformative experiences for audiences.

The god’s dual nature—bringing both joy and destruction—reflected ancient Greek understanding of life’s fundamental paradoxes. Through wine, he offered communion and celebration, yet also warned of excess and loss of control. Through theater, he provided cathartic entertainment while exploring society’s deepest conflicts and contradictions.

The Eternal Dance Between Order and Chaos

The dual nature of Dionysus continues to fascinate modern audiences because it mirrors our own internal struggles between conformity and rebellion. Consider how contemporary society grapples with similar tensions:

Creative Expression in Modern Times

- Artistic movements that challenge conventional boundaries—from punk rock to abstract expressionism—echo Dionysian principles

- Silicon Valley innovators who disrupt traditional industries embody his spirit of creative destruction

- Social media platforms that unleash both creative potential and destructive chaos reflect his unpredictable influence

The Psychology of Transformation

Dionysus understood what modern psychology confirms: genuine growth requires discomfort. His festivals didn’t just celebrate wine and revelry—they created sacred spaces where participants could:

- Shed social masks and explore authentic identity

- Confront suppressed emotions through cathartic release

- Experience collective unity that transcended individual limitations

- Return transformed to everyday life with renewed perspective

Contemporary Parallels to Ancient Mysteries

Today’s seekers find Dionysian energy in unexpected places:

Music Festivals and Concerts

- Temporary communities where normal social rules suspend

- Collective euphoria that mirrors ancient religious ecstasy

- Transformative experiences that participants carry back to ordinary life

Therapeutic Practices

- Psychedelic therapy exploring consciousness expansion

- Expressive arts therapy using creativity for healing

- Wilderness retreats reconnecting with primal nature

Cultural Movements

- Counterculture movements challenging societal norms

- Spiritual revivals seeking transcendent experiences

- Environmental activism defending wild spaces from over-civilization

The Price of Suppressing the Wild

When societies attempt to completely eliminate Dionysian forces, they often face:

- Creative stagnation and cultural rigidity

- Psychological repression leading to explosive outbursts

- Loss of spiritual vitality and meaning

- Disconnection from natural rhythms and authentic emotions

The god’s ancient wisdom suggests that controlled chaos is preferable to suppressed wildness that eventually erupts destructively. His cult provided sanctioned outlets for forces that, if completely denied, could tear apart the social fabric entirely.